Ancient Earthworks

Henges & Ceremonial Enclosures

Henge monuments typically consist of a roughly circular or oval-shaped earthen bank with an internal ditch surrounding a flat central area of more than 50 m (66 ft) in diameter, usually with a single entrance. A variation of a henge, known as an embanked enclosure, has a sunken or hollowed out central area. Henge monuments are often sited near Passage Tombs, forming part of a ritual landscape or complex; with a variety of other Neolithic and Bronze Age monuments located around and sometimes within the henge itself. They are ceremonial/ritual monuments, dating to the Late Neolithic/Early Bronze Age (c. 2800-1700 BC).

Ceremonial Enclosures date from the later Bronze Age to the Iron Age (c. 1200 BC- 400 AD) and tend to be larger than the earlier henges, often with a diameter of over 150m. Associated ritual or burial monuments are almost always found within their embankments. Ceremonial Enclosures are a defining feature of Royal sites such as the Hill of Tara and Dun Ailinne, where the large earthen banks enclose entire hilltops with multiple monuments contained within. There are also examples of Ceremonial Enclosures with multiple banks such as Rathra, Co. Roscommon.

Linear Earthworks

Cursus monuments date to Late Neolithic/Early Bronze Age (c. 2800-1700 BC) and consist of parallel lines of earthen banks. These banks are usually set around 10m apart and run for at least 100m with some examples being up to 400m long. It is thought that they functioned as ceremonial route-ways, forming part of ritual landscapes such as the Hill of Tara and the Boyne Valley complex. The term ‘cursus’ comes from the latin for ‘course’ as it was originally thought they were used for athletics, races, etc.

In the later Bronze and Iron Ages (c. 1200 BC - AD 500) we see the construction of huge linear earthworks that sometimes run for miles across the countryside. They appear to have formed territorial boundaries and/or impediments to cattle raiding. In mythology they are often said to have been created by a huge black pig, hence names such as the Black Pig's Dyke & The Mucklaghs (Drove of Pigs).

Barrows

The appearance of Barrows in Ireland in the Early Bronze Age marks a departure from the long-standing tradition of large collective burial monuments in favour of single burials. Barrows are circular or oval enclosures of earthen construction, typically less than 30m in diameter, with central mound created from material excavated from the surrounding ditch.

The most common are Ring barrows, which have a central mound surrounded by an enclosing ditch with a surrounding outer bank. Bowl-Barrows have a raised central mound, like an inverted bowl, an external ditch and sometimes an outer bank. Ditch-Barrows have a level or slightly raised central area defined by a ditch. The other four types (Mound, Pond, Embanked and Stepped Barrows) have no enclosing ditch. They are distinguished by their characteristic central area and outer bank; with the exception of mound barrows which have no outer bank.

Barrow construction began in the Late-Neolithic, continuing throughout the Bronze-Age and into the Iron-Age when they became the most common form of burial monument. There are over 3000 identified Barrow monuments in Ireland of various forms.

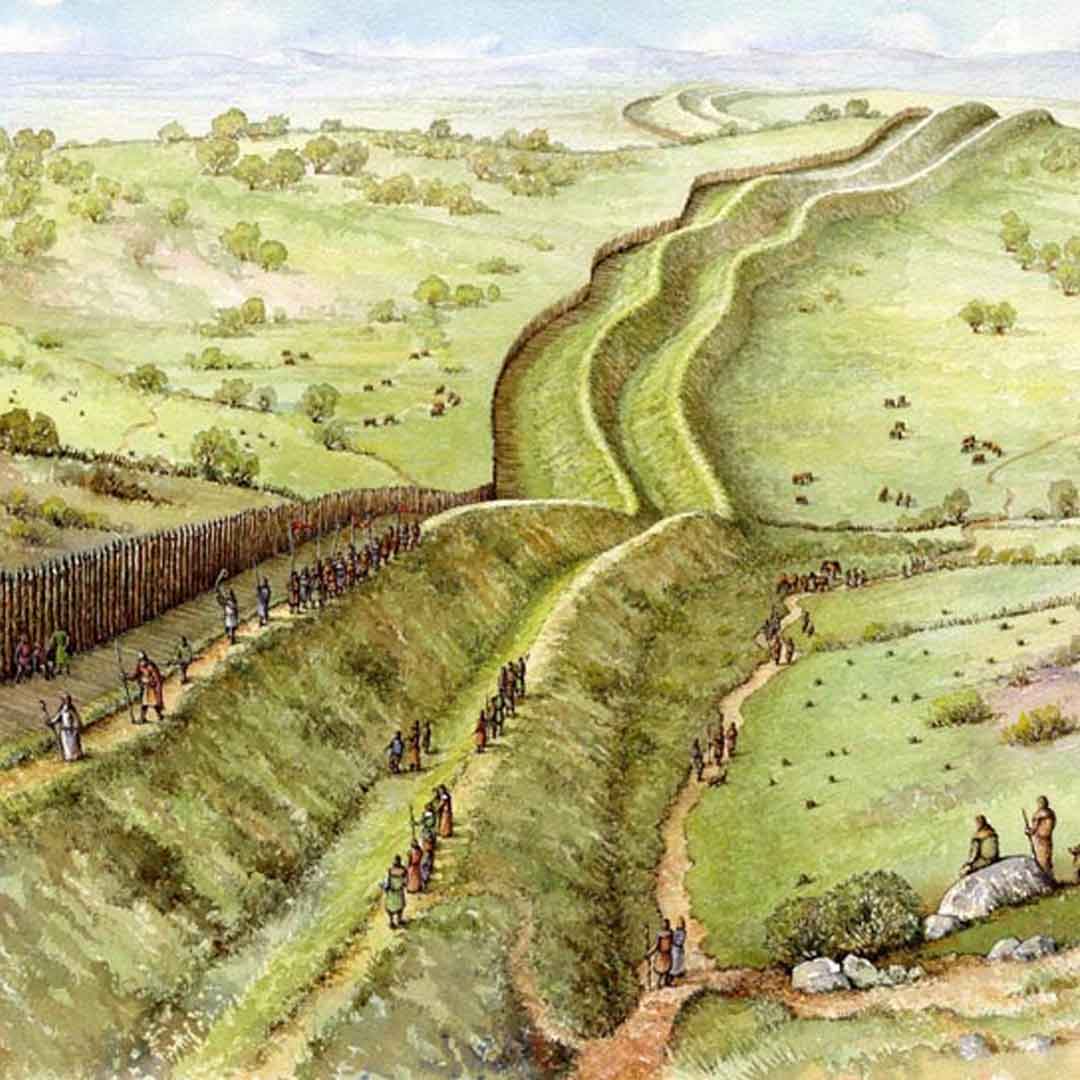

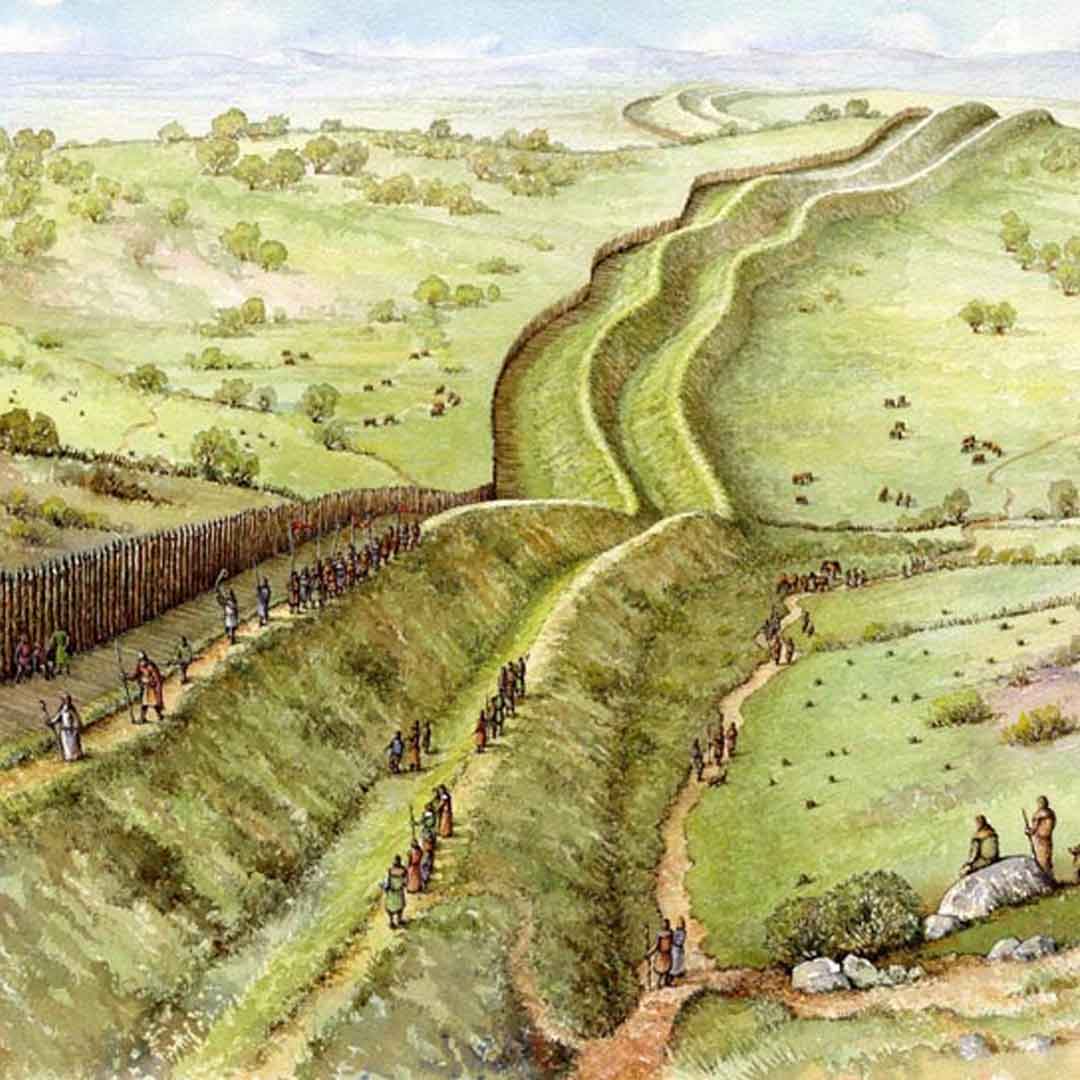

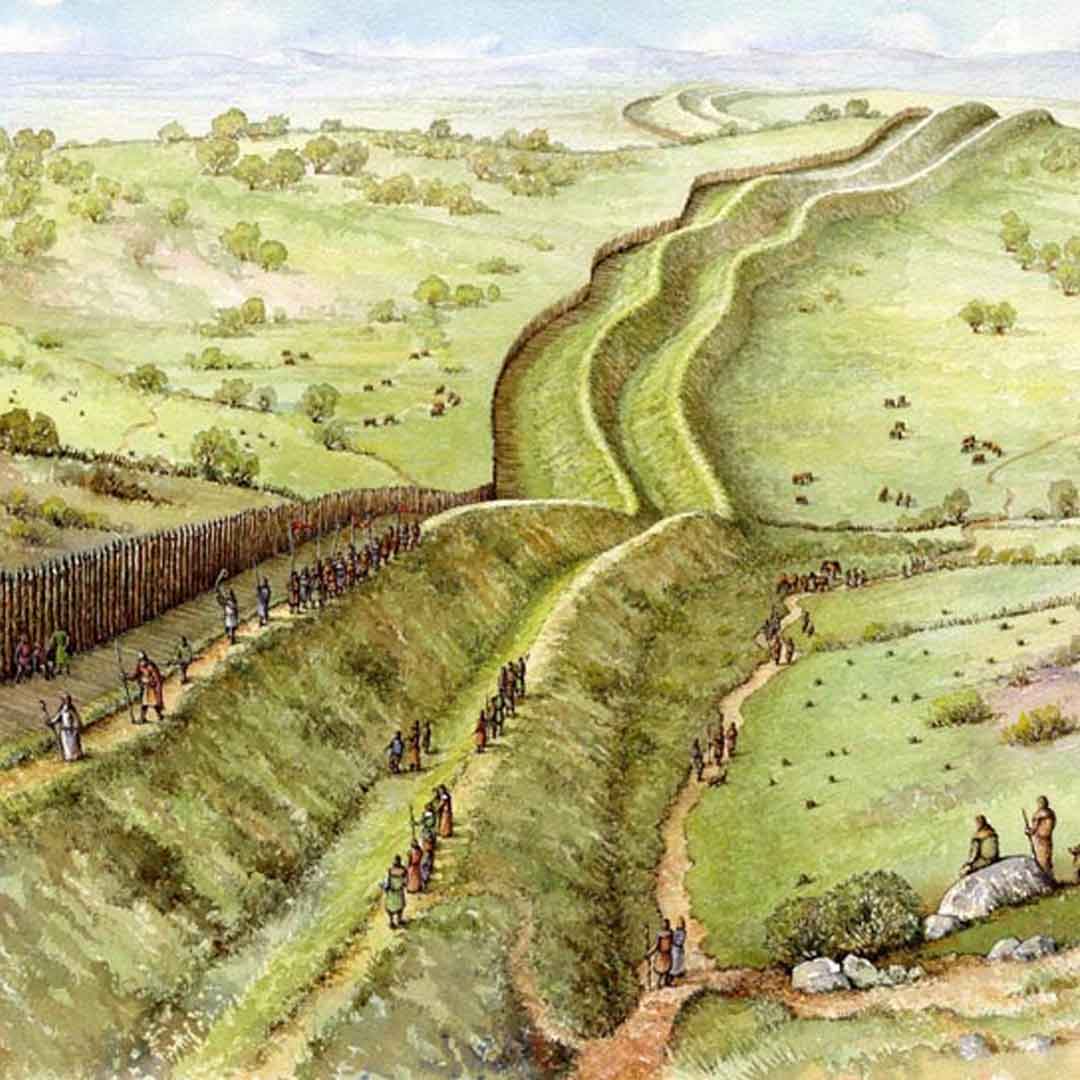

Linear earthwork leading toward the ceremonial enclosure on the Hill of Tara.

Image: National Monuments Service

The majority of barrows contain a single burial in the central area, often in a pit or, in the case of some larger barrows, a ‘cist’ (stone box) beneath the mound. However, many barrows were found to have secondary deposits of cremated remains in the surrounding banks or ditches, perhaps indicating an ancestral lineage.

Often found in clusters of up to 50 individual monuments, these ‘barrow cemeteries’ may represent the funerary sites of large communities. The siting of barrows within larger ceremonial enclosures is also a feature of this monumental tradition.

These various ancient Earthworks were part of the ritual landscape for a very long period, extending from the Late Neolithic through the Bronze-Age and into the Iron Age. In fact, their role as focal points for ritual activity within the landscape has in some cases, such as the Royal/Inauguration sites, persisted long after the arrival of Christianity in the 5th Century AD.

Check out the examples of Earthworks below or click here to view all

Examples of Earthworks

Ancient Earthworks

Henges & Ceremonial Enclosures

Henge monuments typically consist of a roughly circular or oval-shaped earthen bank with an internal ditch surrounding a flat central area of more than 50 m (66 ft) in diameter, usually with a single entrance. A variation of a henge, known as an embanked enclosure, has a sunken or hollowed out central area. Henge monuments are often sited near Passage Tombs, forming part of a ritual landscape or complex; with a variety of other Neolithic and Bronze Age monuments located around and sometimes within the henge itself. They are ceremonial/ritual monuments, dating to the Late Neolithic/Early Bronze Age (c. 2800-1700 BC).

Ceremonial Enclosures date from the later Bronze Age to the Iron Age (c. 1200 BC- 400 AD) and tend to be larger than the earlier henges, often with a diameter of over 150m. Associated ritual or burial monuments are almost always found within their embankments. Ceremonial Enclosures are a defining feature of Royal sites such as the Hill of Tara and Dun Ailinne, where the large earthen banks enclose entire hilltops with multiple monuments contained within. There are also examples of Ceremonial Enclosures with multiple banks such as Rathra, Co. Roscommon.

Linear Earthworks

Cursus monuments date to Late Neolithic/Early Bronze Age (c. 2800-1700 BC) and consist of parallel lines of earthen banks. These banks are usually set around 10m apart and run for at least 100m with some examples being up to 400m long. It is thought that they functioned as ceremonial route-ways, forming part of ritual landscapes such as the Hill of Tara and the Boyne Valley complex. The term ‘cursus’ comes from the latin for ‘course’ as it was originally thought they were used for athletics, races, etc.

In the later Bronze and Iron Ages (c. 1200 BC - AD 500) we see the construction of huge linear earthworks that sometimes run for miles across the countryside. They appear to have formed territorial boundaries and/or impediments to cattle raiding. In mythology they are often said to have been created by a huge black pig, hence names such as the Black Pig's Dyke & The Mucklaghs (Drove of Pigs).

Barrows

The appearance of Barrows in Ireland in the Early Bronze Age marks a departure from the long-standing tradition of large collective burial monuments in favour of single burials. Barrows are circular or oval enclosures of earthen construction, typically less than 30m in diameter, with central mound created from material excavated from the surrounding ditch.

The most common are Ring barrows, which have a central mound surrounded by an enclosing ditch with a surrounding outer bank. Bowl-Barrows have a raised central mound, like an inverted bowl, an external ditch and sometimes an outer bank. Ditch-Barrows have a level or slightly raised central area defined by a ditch. The other four types (Mound, Pond, Embanked and Stepped Barrows) have no enclosing ditch. They are distinguished by their characteristic central area and outer bank; with the exception of mound barrows which have no outer bank.

Barrow construction began in the Late-Neolithic, continuing throughout the Bronze-Age and into the Iron-Age when they became the most common form of burial monument. There are over 3000 identified Barrow monuments in Ireland of various forms.

Linear earthwork leading toward the ceremonial enclosure on the Hill of Tara.

Image: National Monuments Service

The majority of barrows contain a single burial in the central area, often in a pit or, in the case of some larger barrows, a ‘cist’ (stone box) beneath the mound. However, many barrows were found to have secondary deposits of cremated remains in the surrounding banks or ditches, perhaps indicating an ancestral lineage.

Often found in clusters of up to 50 individual monuments, these ‘barrow cemeteries’ may represent the funerary sites of large communities. The siting of barrows within larger ceremonial enclosures is also a feature of this monumental tradition.

These various ancient Earthworks were part of the ritual landscape for a very long period, extending from the Late Neolithic through the Bronze-Age and into the Iron Age. In fact, their role as focal points for ritual activity within the landscape has in some cases, such as the Royal/Inauguration sites, persisted long after the arrival of Christianity in the 5th Century AD.

Check out the examples of Earthworks below or click here to view all

Examples of Earthworks

Ancient Earthworks

Henges & Ceremonial Enclosures

Henge monuments typically consist of a roughly circular or oval-shaped earthen bank with an internal ditch surrounding a flat central area of more than 50 m (66 ft) in diameter, usually with a single entrance. A variation of a henge, known as an embanked enclosure, has a sunken or hollowed out central area. Henge monuments are often sited near Passage Tombs, forming part of a ritual landscape or complex; with a variety of other Neolithic and Bronze Age monuments located around and sometimes within the henge itself. They are ceremonial/ritual monuments, dating to the Late Neolithic/Early Bronze Age (c.2800-1700 BC).

Ceremonial Enclosures date from the later Bronze Age to the Iron Age (c.1200 BC- 400 AD) and tend to be larger than the earlier henges, often with a diameter of over 150m. Associated ritual or burial monuments are almost always found within their embankments. Ceremonial Enclosures are a defining feature of Royal sites such as the Hill of Tara and Dun Ailinne, where the large earthen banks enclose entire hilltops with multiple monuments contained within. There are also examples of Ceremonial Enclosures with multiple banks such as Rathra, Co. Roscommon.

Linear Earthworks

Cursus monuments date to Late Neolithic/Early Bronze Age (c.2800-1700 BC) and consist of parallel lines of earthen banks. These banks are usually set around 10m apart and run for at least 100m with some examples being up to 400m long. It is thought that they functioned as ceremonial route-ways, forming part of ritual landscapes such as the Hill of Tara and the Boyne Valley complex. The term ‘cursus’ comes from the latin for ‘course’ as it was originally thought they were used for athletics, races, etc.

In the later Bronze and Iron Ages (c.1200 BC - AD 500) we see the construction of huge linear earthworks that sometimes run for miles across the countryside. They appear to have formed territorial boundaries and/or impediments to cattle raiding. In mythology they are often said to have been created by a huge black pig, hence names such as the Black Pig's Dyke & The Mucklaghs (Drove of Pigs).

Barrows

The appearance of Barrows in Ireland in the Early Bronze Age marks a departure from the long-standing tradition of large collective burial monuments in favour of single burials. Barrows are circular or oval enclosures of earthen construction, typically less than 30m in diameter, with central mound created from material excavated from the surrounding ditch.

The most common are Ring barrows, which have a central mound surrounded by an enclosing ditch with a surrounding outer bank. Bowl-Barrows have a raised central mound, like an inverted bowl, an external ditch and sometimes an outer bank. Ditch-Barrows have a level or slightly raised central area defined by a ditch. The other four types (Mound, Pond, Embanked and Stepped Barrows) have no enclosing ditch. They are distinguished by their characteristic central area and outer bank; with the exception of mound barrows which have no outer bank.

Barrow construction began in the Late-Neolithic, continuing throughout the Bronze-Age and into the Iron-Age when they became the most common form of burial monument. There are over 3000 identified Barrow monuments in Ireland of various forms.

Linear earthwork leading toward the ceremonial enclosure on the Hill of Tara.

Image: National Monuments Service

The majority of barrows contain a single burial in the central area, often in a pit or, in the case of some larger barrows, a ‘cist’ (stone box) beneath the mound. However, many barrows were found to have secondary deposits of cremated remains in the surrounding banks or ditches, perhaps indicating an ancestral lineage.

Often found in clusters of up to 50 individual monuments, these ‘barrow cemeteries’ may represent the funerary sites of large communities. The siting of barrows within larger ceremonial enclosures is also a feature of this monumental tradition.

These various ancient Earthworks were part of the ritual landscape for a very long period, extending from the Late Neolithic through the Bronze-Age and into the Iron Age. In fact, their role as focal points for ritual activity within the landscape has in some cases, such as the Royal/Inauguration sites, persisted long after the arrival of Christianity in the 5th Century AD.

Check out the examples of Earthworks below or click here to view all